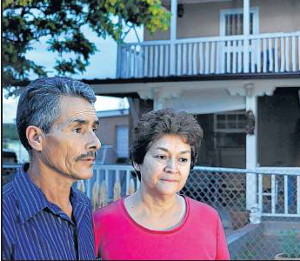

A Chimayó, New Mexico couple fought in court for years over their home foreclosure. Their attorney was Joshua Simms of Albuquerque.

And, in the end, they won. The Supreme Court’s opinion says:”We hold that the Bank of New York did not establish its lawful standing in this case to file a home mortgage foreclosure action.

Bank of New York v. Romero

320 P.3d 1 (2014)

2014-NMSC-007

Supreme Court of New Mexico.

BANK OF NEW YORK as Trustee for Popular Financial Services Mortgage/Pass Through Certificate Series # 2006, Plaintiff–Respondent, v. Joseph A. ROMERO and Mary Romero, a/k/a Mary O. Romero, a/k/a Maria Romero, Defendants–Petitioners.

No. 33,224.

Decided: February 13, 2014

Joshua R. Simms, P.C., Joshua R. Simms, Albuquerque, NM, Frederick M. Rowe, Daniel Yohalem, Katherine Elizabeth Murray, Santa Fe, NM, for Petitioners.

Rose Little Brand & Associates, P.C., Eraina Marie Edwards, Albuquerque, NM, Severson & Werson, Jan T. Chilton, San Francisco, CA, for Respondents.

Gary K. King, Attorney General, Joel Cruz–Esparza, Assistant Attorney General, Karen J. Meyers, Assistant Attorney General, Santa Fe, NM, for Amicus Curiae New Mexico Attorney General.

Nancy Ana Garner, Santa Fe, NM, for Amicus Curiae Civic Amici.

Rodey, Dickason, Sloan, Akin & Robb, P.A., Edward R. Ricco, John P. Burton, Albuquerque, NM, James J. White, Ann Arbor, MI, for Amicus Curiae New Mexico Bankers Association.

OPINION

{1} We granted certiorari to review recurring procedural and substantive issues in home mortgage foreclosure actions. We hold that the Bank of New York did not establish its lawful standing in this case to file a home mortgage foreclosure action. We also hold that a borrower’s ability to repay a home mortgage loan is one of the “borrower’s circumstances” that lenders and courts must consider in determining compliance with the New Mexico Home Loan Protection Act, NMSA 1978, §§ 58–21A–1 to –14 (2003, as amended through 2009) (the HLPA), which prohibits home mortgage refinancing that does not provide a reasonable, tangible net benefit to the borrower. Finally, we hold that the HLPA is not preempted by federal law. We reverse the Court of Appeals and district court and remand to the district court with instructions to vacate its foreclosure judgment and to dismiss the Bank of New York’s foreclosure action for lack of standing.

- FACTUAL AND PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND

{2} On June 26, 2006, Joseph and Mary Romero signed a promissory note with Equity One, Inc. to borrow $227,240 to refinance their Chimayo home. As security for the loan, the Romeros signed a mortgage contract with the Mortgage Electronic Registration Systems (MERS), as the nominee for Equity One, pledging their home as collateral for the loan.

{3} The Romeros allege that Equity One cold-called them and urged them to refinance their home for access to their home’s equity. The terms of the Equity One loan were not an improvement over their current home loan: Equity One’s interest rate was higher (starting at 8.1 percent and increasing to 14 percent compared to 7.71 percent), the Romeros’ monthly payments were greater ($1,683.28 compared to $1,256.39), and the loan amount due was greater ($227,240 compared to $176,450). However, the Romeros would receive a cash payout of nearly $43,000, which would cover about $12,000 in new closing costs and provide them with about $30,000 to pay off other debts.

{4} Both parties agree that the Romeros’ loan was a no income, no assets loan (NINA) and that documentation of their income was never requested or verified. The Romeros owned a music store in Espanola, New Mexico, and Mr. Romero allegedly told Equity One that the store provided him an income of $5,600 a month. Also known as liar loans because they are based solely on the professed income of the self-employed, NINA loans have since been specifically prohibited in New Mexico by a 2009 amendment to the HLPA and also by federal law. See NMSA 1978, § 58–21A–4(C)–(D) (requiring a creditor to document a borrower’s ability to repay); 15 U.S.C.A. § 1639c(a)(1) (2010) (requiring creditors to make a reasonable and good-faith effort to determine a borrower’s ability to repay); see also Pub.L. No. 111–203, § 1411(a)(1), 124 Stat. 2142 (2010) (same). The Romeros stated that they did not read the note or the mortgage contracts thoroughly before signing them, allegedly because of limited time for review, the complexity of the documents, and their own limited education. They admit having signed a document prepared by Equity One reciting that the home loan provided them a “reasonable tangible net benefit” based on the $30,000 cash payout.

{5} The Romeros soon became delinquent on their increased loan payments. On April 1, 2008, a third party—the Bank of New York, identifying itself as a trustee for Popular Financial Services Mortgage—filed a complaint in the First Judicial District Court seeking foreclosure on the Romeros’ home and claiming to be the holder of the Romeros’ note and mortgage with the right of enforcement.

{6} The Romeros responded by arguing, among other things, that the Bank of New York lacked standing to foreclose because nothing in the complaint established how the Bank of New York was a holder of the note and mortgage contracts the Romeros signed with Equity One. According to the Romeros, Securities and Exchange Commission filings showed that their loan certificate series was once owned by Popular ABS Mortgage and not Popular Financial Services Mortgage and that the holder was JPMorgan Chase. The Romeros also raised several counterclaims, only one of which is relevant to this appeal: that the loan violated the antiflipping provisions of the New Mexico HLPA, Section 58–21 A–4(B) (2003).

{7} The Bank responded by providing (1) a document showing that MERS as a nominee for Equity One assigned the Romeros’ mortgage to the Bank of New York on June 25, 2008, three months after the Bank filed the foreclosure complaint and (2) the affidavit of Ann Kelley, senior vice president for Litton Loan Servicing LP, stating that Equity One intended to transfer the note and assign the mortgage to the Bank of New York prior to the Bank’s filing of the foreclosure complaint. However, the Bank of New York admits that Kelley’s employer Litton Loan Servicing did not begin servicing the Romeros’ loan until November 1, 2008, seven months after the foreclosure complaint was filed in district court.

{8} At a bench trial, Kevin Flannigan, a senior litigation processor for Litton Loan Servicing, testified on behalf of the Bank of New York. Flannigan asserted that the copies of the note and mortgage admitted as trial evidence by the Bank of New York were copies of the originals and also testified that the Bank of New York had physical possession of both the note and mortgage at the time it filed the foreclosure complaint.

{9} The Romeros objected to Flannigan’s testimony, arguing that he lacked personal knowledge to make these claims given that Litton Loan Servicing was not a servicer for the Bank of New York until after the foreclosure complaint was filed and the MERS assignment occurred. The district court allowed the testimony based on the business records exception because Flannigan was the present custodian of records.

{10} The Romeros also pointed out that the copy of the “original” note Flannigan purportedly authenticated was different from the “original” note attached to the Bank of New York’s foreclosure complaint. While the note attached to the complaint as a true copy was not indorsed, the “original” admitted at trial was indorsed twice: first, with a blank indorsement by Equity One and second, with a special indorsement made payable to JPMorgan Chase. When asked whether either of those two indorsements included the Bank of New York, Flannigan conceded that neither did, but he claimed that his review of the records indicated the note had been transferred to the Bank of New York based on a pooling and servicing agreement document that was never entered into evidence.

{11} The district court also heard testimony on the circumstances of the loan, the points and fees charged, and the calculus used to determine a reasonable, tangible net benefit. Following trial, the district court issued a written order finding that the Flannigan testimony and the assignment of the mortgage established the Bank of New York as the proper holder of the Romeros’ note and concluding that the loan did not violate the HLPA because the cash payment to the Romeros provided a reasonable, tangible net benefit. The district court also determined that because the Bank of New York was a national bank, federal law preempted the protections of the HLPA.

{12} On appeal, the Court of Appeals affirmed the district court’s rulings that the Bank of New York had standing to foreclose and that the HLPA had not been violated but determined as a result of the latter ruling that it was not necessary to address whether federal law preempted the HLPA. See Bank of N.Y. v. Romero, 2011–NMCA–110, ¶ 6, 150 N.M. 769, 266 P.3d 638 (“Because we conclude that substantial evidence exists for each of the district court’s findings and conclusions, and we affirm on those grounds, we do not address the Romeros’ preemption argument.”).

{13} We granted the Romeros’ petition for writ of certiorari.

- DISCUSSION

- The Bank of New York Lacks Standing to Foreclose

- Preservation

{14} As a preliminary matter, we address the Bank of New York’s argument that the Romeros waived their challenge of the Bank’s standing in this Court and the Court of Appeals by failing to provide the evidentiary support required by Rule 12–213(A)(3) NMRA. See Bank of N.Y., 2011–NMCA–110, ¶¶ 20–21 (dismissing the Romeros’ challenge to standing as without authority and based primarily on the note’s bearer-stamp assignment to JPMorgan Chase); see also Rule 12–213(A)(3) (“A contention that a verdict, judgment or finding of fact is not supported by substantial evidence shall be deemed waived unless the summary of proceedings includes the substance of the evidence bearing upon the proposition.”).

{15} We have recognized that “the lack of [standing] is a potential jurisdictional defect which ‘may not be waived and may be raised at any stage of the proceedings, even sua sponte by the appellate court.’ “ Gunaji v. Macias, 2001–NMSC–028, ¶ 20, 130 N.M. 734, 31 P.3d 1008 (citation omitted). While we disagree that the Romeros waived their standing claim, because their challenge has been and remains largely based on the note’s indorsement to JPMorgan Chase, whether the Romeros failed to fully develop their standing argument before the Court of Appeals is immaterial. This Court may reach the issue of standing based on prudential concerns. See New Energy Economy, Inc. v. Shoobridge, 2010–NMSC–049, ¶ 16, 149 N.M. 42, 243 P.3d 746 (“Indeed, ‘prudential rules’ of judicial self-governance, like standing, ripeness, and mootness, are ‘founded in concern about the proper—and properly limited—role of courts in a democratic society’ and are always relevant concerns.” (citation omitted)). Accordingly, we address the merits of the standing challenge.

- Standards of Review

{16} The Bank argues that under a substantial evidence standard of review, it presented sufficient evidence to the district court that it had the right to enforce the Romeros’ promissory note based primarily on its possession of the note, the June 25, 2008, assignment letter by MERS, and the trial testimony of Kevin Flannigan. By contrast, the Romeros argue that none of the Bank’s evidence demonstrates standing because

(1) possession alone is insufficient,

(2) the “original” note introduced by the Bank of New York at trial with the two undated indorsements includes a special indorsement to JPMorgan Chase, which cannot be ignored in favor of the blank indorsement,

(3) the June 25, 2008, assignment letter from MERS occurred after the Bank of New York filed its complaint, and as a mere assignment of the mortgage does not act as a lawful transfer of the note, and

(4) the statements by Ann Kelley and Kevin Flannigan are inadmissible because both lack personal knowledge given that Litton Loan Servicing did not begin servicing loans for the Bank of New York until seven months after the foreclosure complaint was filed and after the purported transfer of the loan occurred.

For the following reasons, we agree with the Romeros.

{17} The Bank of New York does not dispute that it was required to demonstrate under New Mexico’s Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) that it had standing to bring a foreclosure action at the time it filed suit. See NMSA 1978, § 55–3–301 (1992) (defining who is entitled to enforce a negotiable interest such as a note); see also NMSA 1978, § 55–3–104(a), (b), (e) (1992) (identifying a promissory note as a negotiable instrument); ACLU of N.M. v. City of Albuquerque, 2008–NMSC–045, ¶ 9 n. 1, 144 N.M. 471, 188 P.3d 1222 (recognizing standing as a jurisdictional prerequisite for a statutory cause of action); Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife, 504 U.S. 555, 570–71 n. 5 (1992) ( “[S]tanding is to be determined as of the commencement of suit.”); accord 55 Am.Jur.2d Mortgages § 584 (2009) (“A plaintiff has no foundation in law or fact to foreclose upon a mortgage in which the plaintiff has no legal or equitable interest.”). One reason for such a requirement is simple: “One who is not a party to a contract cannot maintain a suit upon it. If [the entity] was a successor in interest to a party on the [contract], it was incumbent upon it to prove this to the court.” L.R. Prop. Mgmt., Inc. v. Grebe, 1981–NMSC–035, ¶ 7, 96 N.M. 22, 627 P.2d 864 (citation omitted). The Bank of New York had the burden of establishing timely ownership of the note and the mortgage to support its entitlement to pursue a foreclosure action. See Gonzales v. Tama, 1988–NMSC016, ¶ 7, 106 N.M. 737, 749 P.2d 1116 (“One who holds a note secured by a mortgage has two separate and independent remedies, which he may pursue successively or concurrently; one is on the note against the person and property of the debtor, and the other is by foreclosure to enforce the mortgage lien upon his real estate.” (internal quotation marks and citation omitted)).

{18} Because the district court determined after a trial on the issue that the Bank of New York established standing as a factual matter, we review the district court’s determination under a substantial evidence standard of review. See Sims v. Sims, 1996–NMSC–078, ¶ 65, 122 N.M. 618, 930 P.2d 153 (“We have many times stated the standard of review of a trial court’s findings of fact: Findings of fact made by the district court will not be disturbed if they are supported by substantial evidence.”). “ ‘Substantial evidence’ means relevant evidence that a reasonable mind could accept as adequate to support a conclusion.” Id. “This Court will resolve all disputed facts and indulge all reasonable inferences in favor of the trial court’s findings.” Id. However, “[w]hen the resolution of the issue depends upon the interpretation of documentary evidence, this Court is in as good a position as the trial court to interpret the evidence.” Kirkpatrick v. Introspect Healthcare Corp., 1992–NMSC–070, ¶ 14, 114 N.M. 706, 845 P.2d 800; see also United Nuclear Corp. v. Gen. Atomic Co., 1979–NMSC–036, ¶ 62, 93 N.M. 105, 597 P.2d 290 (“ ‘Where all or substantially all of the evidence on a material issue is documentary or by deposition, the Supreme Court will examine and weigh it, and will review the record, giving some weight to the findings of the trial judge on such issue.’ “ (citation omitted)).

- None of the Bank’s Evidence Demonstrates Standing to Foreclose

{19} The Bank of New York argues that in order to demonstrate standing, it was required to prove that before it filed suit, it either (1) had physical possession of the Romeros’ note indorsed to it or indorsed in blank or (2) received the note with the right to enforcement, as required by the UCC. See § 55–3–301 (defining “[p]erson entitled to enforce” a negotiable instrument). While we agree with the Bank that our state’s UCC governs how a party becomes legally entitled to enforce a negotiable instrument such as the note for a home loan, we disagree that the Bank put forth such evidence.

- Possession of a Note Specially Indorsed to JPMorgan Chase Does Not Establish the Bank of New York as a Holder

{20} Section 55–3–301 of the UCC provides three ways in which a third party can enforce a negotiable instrument such as a note. Id. (“ ‘Person entitled to enforce’ an instrument means

(i) the holder of the instrument,

(ii) a nonholder in possession of the instrument who has the rights of a holder, or

(iii) (iii) a person not in possession of the instrument who is entitled to enforce the [lost, destroyed, stolen, or mistakenly transferred] instrument pursuant to [certain UCC enforcement provisions].”); see also § 55–3–104(a)(1), (b), (e) (defining “negotiable instrument” as including a “note” made “payable to bearer or to order”).

Because the Bank’s arguments rest on the fact that it was in physical possession of the Romeros’ note, we need to consider only the first two categories of eligibility to enforce under Section 55–3–301.

{21} The UCC defines the first type of “person entitled to enforce” a note—the “holder” of the instrument—as “the person in possession of a negotiable instrument that is payable either to bearer or to an identified person that is the person in possession.” NMSA 1978, § 55–1–201(b)(21)(A) (2005); see also Frederick M. Hart & William F. Willier, Negotiable Instruments Under the Uniform Commercial Code, § 12.02(1) at 12–13 to 12–15 (2012) (“The first requirement of being a holder is possession of the instrument.

However, possession is not necessarily sufficient to make one a holder․ The payee is always a holder if the payee has possession. Whether other persons qualify as a holder depends upon whether the instrument initially is payable to order or payable to bearer, and whether the instrument has been indorsed.” (footnotes omitted)). Accordingly, a third party must prove both physical possession and the right to enforcement through either a proper indorsement or a transfer by negotiation. See NMSA 1978, § 55–3–201(a) (1992) (“ ‘Negotiation’ means a transfer of possession ․ of an instrument by a person other than the issuer to a person who thereby becomes its holder.”). Because in this case the Romeros’ note was clearly made payable to the order of Equity One, we must determine whether the Bank provided sufficient evidence of how it became a “holder” by either an indorsement or transfer.

{22} Without explanation, the note introduced at trial differed significantly from the original note attached to the foreclosure complaint, despite testimony at trial that the Bank of New York had physical possession of the Romeros’ note from the time the foreclosure complaint was filed on April 1, 2008. Neither the unindorsed note nor the twice-indorsed note establishes the Bank as a holder.

{23} Possession of an unindorsed note made payable to a third party does not establish the right of enforcement, just as finding a lost check made payable to a particular party does not allow the finder to cash it. See NMSA 1978, § 55–3–109 cmt. 1 (1992) (“An instrument that is payable to an identified person cannot be negotiated without the indorsement of the identified person.”). The Bank’s possession of the Romeros’ unindorsed note made payable to Equity One does not establish the Bank’s entitlement to enforcement.

{24} The Bank’s possession of a note with two indorsements, one of which restricts payment to JPMorgan Chase, also does not establish the Bank’s entitlement to enforcement. The UCC recognizes two types of indorsements for the purposes of negotiating an instrument. A blank indorsement, as its name suggests, does not identify a person to whom the instrument is payable but instead makes it payable to anyone who holds it as bearer paper. See NMSA 1978, § 55–3–205(b) (1992) (“If an indorsement is made by the holder of an instrument and it is not a special indorsement, it is a ‘blank indorsement.’ ”). “When indorsed in blank, an instrument becomes payable to bearer and may be negotiated by transfer of possession alone until specially indorsed.” Id.

{25} By contrast, a special indorsement “identifies a person to whom it makes the instrument payable.” Section 55–3–205(a). “When specially indorsed, an instrument becomes payable to the identified person and may be negotiated only by the indorsement of that person.” Id.; accord Baxter Dunaway, Law of Distressed Real Estate, § 24:105 (2011) (“When an instrument is payable to an identified person, only that person may be the holder. A person in possession of an instrument not made payable to his order can only become a holder by obtaining the prior holder’s indorsement.”).

{26} The trial copy of the Romeros’ note contained two undated indorsements: a blank indorsement by Equity One and a special indorsement by Equity One to JPMorgan Chase. Although we agree with the Bank that if the Romeros’ note contained only a blank indorsement from Equity One, that blank indorsement would have established the Bank as a holder because the Bank would have been in possession of bearer paper, that is not the situation before us. The Bank’s copy of the Romeros’ note contained two indorsements, and the restrictive, special indorsement to JPMorgan Chase establishes JPMorgan Chase as the proper holder of the Romeros’ note absent some evidence by JPMorgan Chase to the contrary. See Cadle Co. v. Wallach Concrete, Inc., 1995–NMSC–039, ¶ 14, 120 N.M. 56, 897 P.2d 1104 (“[A] special indorser ․ has the right to direct the payment and to require the indorsement of his indorsee as evidence of the satisfaction of own obligation. Without such an indorsement, a transferee cannot qualify as a holder in due course.” (omission in original) (internal quotation marks and citation omitted)). Because JPMorgan Chase did not subsequently indorse the note, either in blank or to the Bank of New York, the Bank of New York cannot establish itself as the holder of the Romeros’ note simply by possession.

{27} Rather than demonstrate timely ownership of the note and mortgage through JPMorgan Chase, the Bank of New York urges this Court to infer that the special indorsement was a mistake and that we should rely only on the blank indorsement. We are not persuaded. The Bank provides no authority and we know of none that exists to support its argument that the payment restrictions created by a special indorsement can be ignored contrary to our long-held rules on indorsements and the rights they create. See, e.g., id. (rejecting each of two entities as a holder because a note lacked the requisite indorsement following a special indorsement); accord NMSA 1978, § 55–3–204(c) (1992) ( “For the purpose of determining whether the transferee of an instrument is a holder, an indorsement that transfers a security interest in the instrument is effective as an unqualified indorsement of the instrument.”).

{28} Accordingly, we conclude that the Bank of New York’s possession of the twice-indorsed note restricting payment to JPMorgan Chase does not establish the Bank of New York as a holder with the right of enforcement.

- None of the Bank of New York’s Evidence Demonstrates a Transfer of the Romeros’ Note

{29} The second type of “person entitled to enforce” a note under the UCC is a third party in possession who demonstrates that it was given the rights of a holder. See § 55–3–301 (“ ‘Person entitled to enforce’ an instrument means ․ a nonholder in possession of the instrument who has the rights of a holder.”). This provision requires a nonholder to prove both possession and the transfer of such rights. See NMSA 1978, § 55–3–203(a)–(b) (1992) (defining what constitutes a transfer and vesting in a transferee only those rights held by the transferor). A claimed transferee must establish its right to enforce the note. See § 55–3–203 cmt. 2 (“[An] instrument [unindorsed upon transfer], by its terms, is not payable to the transferee and the transferee must account for possession of the unindorsed instrument by proving the transaction through which the transferee acquired it.”).

{30} Under this second category, the Bank of New York relies on the testimony of Kevin Flannigan, an employee of Litton Loan Servicing who maintained that his review of loan servicing records indicated that the Bank of New York was the transferee of the note. The Romeros objected to Flannigan’s testimony at trial, an objection that the district court overruled under the business records exception. We agree with the Romeros that Flannigan’s testimony was inadmissible and does not establish a proper transfer.

{31} As the Bank of New York admits, Flannigan’s employer, Litton Loan Servicing, did not begin working for the Bank of New York as its servicing agent until November 1, 2008—seven months after the April 1, 2008, foreclosure complaint was filed. Prior to this date, Popular Mortgage Servicing, Inc. serviced the Bank of New York’s loans. Flannigan had no personal knowledge to support his testimony that transfer of the Romeros’ note to the Bank of New York prior to the filing of the foreclosure complaint was proper because Flannigan did not yet work for the Bank of New York. See Rule 11–602 NMRA (“A witness may testify to a matter only if evidence is introduced sufficient to support a finding that the witness has personal knowledge of the matter. Evidence to prove personal knowledge may consist of the witness’s own testimony.”). We make a similar conclusion about the affidavit of Ann Kelley, who also testified about the status of the Romeros’ loan based on her work for Litton Loan Servicing. As with Flannigan’s testimony, such statements by Kelley were inadmissible because they lacked personal knowledge.

{32} When pressed about Flannigan’s basis of knowledge on cross-examination, Flannigan merely stated that “our records do indicate” the Bank of New York as the holder of the note based on “a pooling and servicing agreement.” No such business record itself was offered or admitted as a business records hearsay exception. See Rule 11–803(F) NMRA (2007) (naming this category of hearsay exceptions as “records of regularly conducted activity”).

{33} The district court erred in admitting the testimony of Flannigan as a custodian of records under the exception to the inadmissibility of hearsay for “business records” that are made in the regular course of business and are generally admissible at trial under certain conditions. See Rule 11–803(F) (2007) (citing the version of the rule in effect at the time of trial). The business records exception allows the records themselves to be admissible but not simply statements about the purported contents of the records. See State v. Cofer, 2011–NMCA–085, ¶ 17, 150 N.M. 483, 261 P.3d 1115 (holding that, based on the plain language of Rule 11–803(F) (2007), “it is clear that the business records exception requires some form of document that satisfies the rule’s foundational elements to be offered and admitted into evidence and that testimony alone does not qualify under this exception to the hearsay rule” and concluding that “ ‘testimony regarding the contents of business records, unsupported by the records themselves, by one without personal knowledge of the facts constitutes inadmissible hearsay.’ “ (citation omitted)). Neither Flannigan’s testimony nor Kelley’s affidavit can substantiate the existence of documents evidencing a transfer if those documents are not entered into evidence. Accordingly, Flannigan’s trial testimony cannot establish that the Romeros’ note was transferred to the Bank of New York.

{34} We also reject the Bank’s argument that it can enforce the Romeros’ note because it was assigned the mortgage by MERS. An assignment of a mortgage vests only those rights to the mortgage that were vested in the assigning entity and nothing more. See § 55–3–203(b) (“Transfer of an instrument, whether or not the transfer is a negotiation, vests in the transferee any right of the transferor to enforce the instrument, including any right as a holder in due course.”); accord Hart & Willier, supra, § 12 .03(2) at 12–27 (“Th[is] shelter rule puts the transferee in the shoes of the transferor.”).

{35} Here, as Equity One and MERS explained to the district court in a joint filing seeking to be dismissed as third parties to the Romeros’ counterclaims, “MERS ․ is merely the nominee for Equity One, Inc. in the underlying Mortgage and was not the actual lender. MERS is a national electronic registry which keeps track of the changes in servicing and ownership of mortgage loans.” See also Christopher L. Peterson, Foreclosure, Subprime Mortgage Lending, and the Mortgage Electronic Registration System, 78 U. Cin. L.Rev. 1359, 1361–63 (2010) (explaining that MERS was created by the banking industry to electronically track and record mortgages in order to avoid local and state recording fees). The Romeros’ mortgage contract reiterates the MERS role, describing “MERS [a]s a separate corporation that is acting solely as a nominee for Lender and Lender’s successors and assigns.” A “nominee” is defined as “[a] person designated to act in place of another, usu. in a very limited way.” Black’s Law Dictionary 1149 (9th ed.2009). As a nominee for Equity One on the mortgage contract, MERS could assign the mortgage but lacked any authority to assign the Romeros’ note. Although this Court has never explicitly ruled on the issue of whether the assignment of a mortgage could carry with it the transfer of a note, we have long recognized the separate functions that note and mortgage contracts perform in foreclosure actions. See First Nat’l Bank of Belen v. Luce, 1974–NMSC–098, ¶ 8, 87 N.M. 94, 529 P.2d 760 (holding that because the assignment of a mortgage to a bank did not convey an interest in the loan contract, the bank was not entitled to foreclose on the mortgage); Simson v. Bilderbeck, Inc., 1966–NMSC–170, ¶¶ 13–14, 76 N.M. 667, 417 P.2d 803 (explaining that “[t]he right of the assignee to enforce the mortgage is dependent upon his right to enforce the note” and noting that “[b]oth the note and mortgage were assigned to plaintiff. Having a right under the statute to enforce the note, he could foreclose the mortgage.”); accord 55 Am.Jur.2d Mortgages § 584 (“A mortgage securing the repayment of a promissory note follows the note, and thus, only the rightful owner of the note has the right to enforce the mortgage.”); Dunaway, supra, § 24:18 (“The mortgage only secures the payment of the debt, has no life independent of the debt, and cannot be separately transferred. If the intent of the lender is to transfer only the security interest (the mortgage), this cannot legally be done and the transfer of the mortgage without the debt would be a nullity.”). These separate contractual functions—where the note is the loan and the mortgage is a pledged security for that loan—cannot be ignored simply by the advent of modern technology and the MERS electronic mortgage registry system.

{36} The MERS assignment fails for several additional reasons. First, it does not explain the conflicting special indorsement of the note to JPMorgan Chase. Second, its assignment of the mortgage to the Bank of New York on June 25, 2008, three months after the foreclosure complaint was filed, does not establish a proper transfer prior to the filing date of the foreclosure suit. Third, except for the inadmissible affidavit of Ann Kelley and trial testimony of Kevin Flannigan, nothing in the record substantiates the Bank’s claim that the MERS assignment was meant to memorialize an earlier transfer to the Bank of New York. Accordingly, neither the MERS assignment nor Flannigan’s testimony establish the Bank of New York as a nonholder in possession with the rights of a holder by transfer.

- Failure of Another Entity to Claim Ownership of the Romeros’ Note Does Not Make the Bank of New York a Holder

{37} Finally, the Bank of New York urges this Court to adopt the district court’s inference that if the Bank was not the proper holder of the Romeros’ note, then third-party-defendant Equity One would have claimed to be the rightful holder, and Equity One made no such claim.

{38} The simple fact that Equity One does not claim ownership of the Romeros’ note does not establish that the note was properly transferred to the Bank of New York. In fact, the evidence in the record indicates that JPMorgan Chase may be the lawful holder of the Romeros’ note, as reflected in the note’s special indorsement. As this Court has recognized,

The whole purpose of the concept of a negotiable instrument under Article 3 [of the UCC] is to declare that transferees in the ordinary course of business are only to be held liable for information appearing in the instrument itself and will not be expected to know of any limitations on negotiability or changes in terms, etc., contained in any separate documents.

First State Bank at Gallup v. Clark, 1977–NMSC–088, ¶ 10, 91 N.M. 117, 570 P.2d 1144. In addition, the UCC clarifies that the Bank of New York is not afforded any assumption of enforcement without proper documentation:

Because the transferee is not a holder, there is no presumption under Section [55–] 3–308 [ (1992) (entitling a holder in due course to payment by production and upon signature) ] that the transferee, by producing the instrument, is entitled to payment. The instrument, by its terms, is not payable to the transferee and the transferee must account for possession of the unindorsed instrument by proving the transaction through which the transferee acquired it.

Section 55–3–203 cmt.

- Because the Bank of New York did not introduce any evidence demonstrating that it was a party with the right to enforce the Romeros’ note either by an indorsement or proper transfer, we hold that the Bank’s standing to foreclose on the Romeros’ mortgage was not supported by substantial evidence, and we reverse the contrary determinations of the courts below.

A Lender Must Consider a Borrower’s Ability to Repay a Home Mortgage Loan in Determining Whether the Loan Provides a Reasonable, Tangible Net Benefit, as Required by the New Mexico HLPA

{39} For reasons that are not clear in the record, the Romeros did not appeal the district court’s judgment in favor of the original lender, Equity One, on the Romeros’ claims that Equity One violated the HLPA. The Court of Appeals addressed the HLPA violation issue in the context of the Romeros’ contentions that the alleged violation constituted a defense to the foreclosure complaint of the Bank of New York by affirming the district court’s favorable ruling on the Bank of New York’s complaint. As a result of our holding that the Bank of New York has not established standing to bring a foreclosure action, the issue of HLPA violation is now moot in this case. But because it is an issue that is likely to be addressed again in future attempts by whichever institution may be able to establish standing to foreclose on the Romero home and because it involves a statutory interpretation issue of substantial public importance in many other cases, we address the conclusion of both the Court of Appeals and the district court that a homeowner’s inability to repay is not among “all of the circumstances” that the 2003 HLPA, applicable to the Romeros’ loan, requires a lender to consider under its “flipping” provisions:

No creditor shall knowingly and intentionally engage in the unfair act or practice of flipping a home loan. As used in this subsection, “flipping a home loan” means the making of a home loan to a borrower that refinances an existing home loan when the new loan does not have reasonable, tangible net benefit to the borrower considering all of the circumstances, including the terms of both the new and refinanced loans, the cost of the new loan and the borrower’s circumstances.

Section 58–21A–4(B) (2003); see also Bank of N.Y., 2011–NMCA–110, ¶ 17 (holding that “while the ability to repay a loan is an important consideration when otherwise assessing a borrower’s financial situation, we will not read such meaning into the statute’s ‘reasonable, tangible net benefit’ language”).

{40} “Statutory interpretation is a question of law, which we review de novo.” Hovet v. Allstate Ins. Co., 2004–NMSC–010, ¶ 10, 135 N.M. 397, 89 P.3d 69. “[W]hen presented with a question of statutory construction, we begin our analysis by examining the language utilized by the Legislature, as the text of the statute is the primary indicator of legislative intent.” Bishop v. Evangelical Good Samaritan Soc., 2009–NMSC–036, ¶ 11, 146 N.M. 473, 212 P.3d 361. Under the rules of statutory construction, “[w]hen a statute contains language which is clear and unambiguous, we must give effect to that language and refrain from further statutory interpretation.” State ex rel. Helman v. Gallegos, 1994–NMSC–023, ¶ 18, 117 N.M. 346, 871 P.2d 1352 (internal quotation marks and citation omitted).

{41} The New Mexico Legislature passed the HLPA in 2003 to combat abusive home mortgage procurement practices, with special concerns about non-income-based loans. See § 58–21A–2(A)–(B) (finding that “abusive mortgage lending has become an increasing problem in New Mexico, exacerbating the loss of equity in homes and causing the number of foreclosures to increase in recent years” and that “one of the most common forms of abusive lending is the making of loans that are equity-based, rather than income-based”). “The [HLPA] shall be liberally construed to carry out its purpose.” Section 58–21A–14.

{42} In 2004, regulations were adopted to clarify that “[t]he reasonable, tangible net benefit standard in Section 58–21A–4 B NMSA 1978, is inherently dependent upon the totality of facts and circumstances relating to a specific transaction,” 12.15.5.9(A) NMAC, and that “each lender should develop and maintain policies and procedures for evaluating loans in circumstances where an economic test, standing alone, may not be sufficient to determine that the transaction provides the requisite benefit,” 12.15.5.9(B) NMAC. See also 12.15.5.9(C) NMAC (stating that evaluation of compliance with the HLPA’s loan-flipping provision “will focus on whether a lender has policies and procedures in place ․ that were used to determine that borrowers received a reasonable, tangible net benefit in connection with the refinancing of loans”).

{43} The Court of Appeals expressed that it was significant that the Legislature did not specifically recite the ability to repay as a factor to be considered in the undefined “borrower’s circumstances” addressed in the antiflipping provisions of Section 58–21A–4(B) (2003) while the Legislature did specifically recite that factor in a separate section of the HLPA prohibiting equity stripping in high-cost loans. See Bank of N.Y., 2011–NMCA–110, ¶¶ 11, 17 (noting that the 2003 HLPA “sets forth limitations and prohibited practices for ‘high-cost’ mortgages”); see also § 58–21A–5(H) (2003) (“No creditor shall make a high-cost home loan without due regard to repayment ability.”). The Court of Appeals inferred from the specific additional wording in the 2003 statutory provisions for high-cost loans that “when it enacted Section 58–21A–4(B)” in 2003 the Legislature “chose not to require consideration and documentation of a borrower’s reasonable ability to repay the loan when determining what tangible benefit, if any, the borrower would receive from a mortgage loan.” Bank of N.Y., 2011–NMCA–110, ¶ 17. While comparisons between sections of a statute can be helpful in determining legislative intent where the statutory language or the legislative purpose is unclear, we cannot ignore the commands of either the broad plain language of the HLPA antiflipping provisions, identical in both the 2003 statute and its 2009 amendment and requiring consideration of all circumstances including those of the borrower, or the express legislative purpose declarations of what the HLPA was enacted to avoid, including abusive mortgage loans not based on income that result in the loss of borrowers’ homes. We have been presented with no conceivable reason why the Legislature in 2003 would consciously exclude consideration of a borrower’s ability to repay the loan as a factor of the borrower’s circumstances, and we can think of none. Without an express legislative direction to that effect, we will not conclude that the Legislature meant to approve mortgage loans that were doomed to end in failure and foreclosure. Apart from the plain language of the statute and its express statutory purpose, it is difficult to comprehend how an unrepayable home mortgage loan that will result in a foreclosure on one’s home and a deficiency judgment to pay after the borrower is rendered homeless could provide “a reasonable, tangible net benefit to the borrower.”

{44} In light of the remedial purposes of the HLPA, the broadly inclusive language of the 2003 antiflipping provisions requiring home refinancing to provide a “reasonable, tangible net benefit to the borrower considering all of the circumstances,” and the reiteration in the same sentence that “all of the circumstances” includes specific consideration of “the borrower’s circumstances,” we hold that the ability of a homeowner to have a reasonable chance of repaying a mortgage loan must be a factor in the “reasonable, tangible net benefit” analysis required by the antiflipping provisions of the HLPA since the original 2003 enactment. While it is theoretically possible that other factors of a particular buyer’s individual situation might support a finding of a reasonable, tangible benefit in the totality of the circumstances despite the difficulty a buyer might have repaying the new loan, neither court below considered the Romeros’ ability to repay the loan at all in reviewing the totality of their circumstances, and it is inappropriate for us to make that factual determination on appeal.

{45} Because the Romeros’ mortgage and others like it may come before our courts in the future, we make some observations to provide guidance in assessing a borrower’s ability to repay. The lender in this case claimed to rely solely on the Romeros’ unexplained assertion on a form that they earned $5,600 a month, but the lender did not review tax returns or other documents that easily would have clarified earning $5,600 as a one-time occurrence. The Bank argues that the lender was not required to ask the borrowers for proof of their income but rather that the Romeros were required to provide it, citing 12.15.5.9(G) NMAC (“Borrowers are responsible for the disclosure of information provided on the application for a home loan. Truthful disclosure of all relevant facts and financial information concerning the borrower’s circumstances is required in order for lenders to evaluate and determine that the refinance loan transaction provides a reasonable, tangible net benefit to the borrower.”). But under the very next provision in the regulation, a lender cannot avoid its own obligation to consider real facts and circumstances that might clarify the inaccuracy of a borrower’s income claim. Id. (“Lenders cannot, however, disregard known facts and circumstances that may place in question the accuracy of information contained in the application.”) A lender’s willful blindness to its responsibility to consider the true circumstances of its borrowers is unacceptable. A full and fair consideration of those circumstances might well show that a new mortgage loan would put a borrower into a materially worse situation with respect to the ability to make home loan payments and avoid foreclosure, consequences of a borrower’s circumstances that cannot be disregarded.

{46} We acknowledge that the Romeros signed their names to a document prepared by the lender reciting the conclusion that the loan provided them with a reasonable, tangible net benefit. But if the inclusion of such boilerplate language in the mass of documents a borrower must sign at closing would substitute for a lender’s conscientious compliance with the obligations imposed by the HLPA, its protections would be no more than empty words on paper that could be summarily swept aside by the addition of yet one more document for the borrower to sign at the closing.

{47} The lender’s own benefit analysis questionnaire in this case should have put the lender on notice that the loan might not have provided a reasonable, tangible net benefit.

{48} Step one of the questionnaire required the lender to weigh the Romeros’ new loan against their existing loan and respond to seven questions by comparing factors such as the loans’ monthly payments and interest rates, determining the time between the original loan and the refinancing, and indicating whether the borrower received cash. If the new loan provided five of seven potential benefits as indicated by graded responses to the seven questions, then the lender’s own formula would result in the finding of a reasonable, tangible net benefit and no further evaluation would be necessary. Because the Equity One analysis indicated only one of the seven benefits, net cash to the Romeros at the time of closing, Equity One was not yet authorized by its own policies to make the loan and needed to proceed with step two.

{49} Step two required the lender to (1) provide a written “verification or documentation” that the loan was “appropriate for the borrower” and (2) indicate on a preprinted checklist any of eight reasonable, tangible net benefits the borrower would be receiving. Although Equity One responded to the second requirement by indicating that the loan refinanced some of the Romeros’ debt, it left the first blank, offering no verification that the loan was appropriate for the Romeros based on their ability to repay—a required element of Equity One’s own benefit analysis. Equity One’s benefit analysis worksheet reviewed and approved by an Equity One manager on June 26, 2006, speaks for itself, providing unbiased, documentary evidence of Equity One’s own disregard of the Romeros’ financial circumstances in violation of the HLPA, whether or not the Romeros signed Equity One’s document reciting that they received a reasonable, tangible net benefit. See 12.15.5.9(H) NMAC (“An appropriate analysis reflected in the loan documentation can be helpful in determining that a lender satisfies the statutory requirement. As part of a lender’s analysis, a lender may wish to obtain and document an explanation from the borrower regarding any non-economic benefits the borrower associates with the loan transaction. It should be noted, however, that because it is incumbent on the lender to conduct an analysis of whether the borrower received a reasonable, tangible net benefit, a borrower certification, standing alone, would not necessarily be determinative of whether a loan provided that benefit.”).

{50} Borrowers are certainly not blameless if they try to refinance their homes through loans they cannot afford. But they do not have a mortgage lender’s expertise, and the combination of the relative unsophistication of many borrowers and the potential motives of unscrupulous lenders seeking profits from making loans without regard for the consequences to homeowners led to the need for statutory reform. See § 58–21A–2 (discussing (A) “abusive mortgage lending” practices, including (B) “making ․ loans that are equity-based, rather than income based,” (C) “repeatedly refinanc[ing] home loans,” rewarding lenders with “immediate income” from “points and fees” and (D) victimizing homeowners with the unnecessary “costs and terms” of “overreaching creditors”). The HLPA was enacted to prevent the kinds of practices the Romeros allege Equity One engaged in here: actively soliciting vulnerable homeowners and offering tempting incentives such as up-front cash to induce them to refinance their mortgages with unfavorable terms or without regard for the borrowers’ ability to repay the loans and avoid loss of their homes. Whether the Romeros’ allegations are accurate is not before us, but a court must consider the allegations in order to determine whether the lender violated the HLPA.

- Federal Law Does Not Preempt the Protections of the HLPA

{51} Although the Court of Appeals did not review the conclusion of the district court that federal law preempts the HLPA, see Bank of N.Y., 2011–NMCA–110, ¶ 6, our discussion of the applicability of the HLPA to New Mexico home mortgage loans would be incomplete without our addressing the issue.

{52} “The doctrine of preemption is an outgrowth of the Supremacy Clause of Article VI of the United States Constitution.” Self v. United Parcel Serv., Inc., 1998–NMSC–046, ¶ 7 n. 3, 126 N.M. 396, 970 P.2d 582 (“ ‘This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States ․ shall be the supreme Law of the Land.’ “ (quoting Article VI of the United States Constitution)). “We review issues of statutory and constitutional interpretation de novo .” State v. Lucero, 2007–NMSC–041, ¶ 8, 142 N.M. 102, 163 P.3d 489.

{53} The Bank of New York’s argument that federal law preempts the HLPA relies on regulatory provisions of the New Mexico Regulation and Licensing Department’s Financial Institutions Division recognizing that “[e]ffective February 12, 2004, the [federal Office of the Comptroller of Currency] published a final rule that states, in pertinent part: ‘state laws that obstruct, impair, or condition a national bank’s ability to fully exercise its federally authorized real estate lending powers do not apply to national banks’ (the ‘OCC preemption’)” and concluding that “[b]ased on the OCC preemption, since January 1, 2004, national banks in New Mexico have been authorized to engage in certain banking activities otherwise prohibited by the [HLPA].” 12.16.76.8(G)-(H) NMAC. These administrative provisions have not been updated since 2004. See 12.16.76.8 NMAC (noting only one amendment, on June 15, 2004, since the January 1, 2004, effective date of the regulation).

{54} While the Bank is correct in asserting that the OCC issued a blanket rule in January 2004, see 12 C.F.R. § 34.4(a) (2004) (preempting state laws that impact “a national bank’s ability to fully exercise its Federally authorized real estate lending powers”), and that the New Mexico Administrative Code recognizes this OCC rule, neither the Bank nor our administrative code addresses several actions taken by Congress and the courts since 2004 to disavow the OCC’s broad preemption statement.

{55} In 2007, the United States Supreme Court reiterated its position on preemption by the National Bank Act (NBA), stating that

[i]n the years since the NBA’s enactment, we have repeatedly made clear that federal control shields national banking from unduly burdensome and duplicative state regulation. Federally chartered banks are subject to state laws of general application in their daily business to the extent such laws do not conflict with the letter or the general purposes of the NBA.

Watters v. Wachovia Bank, N.A., 550 U.S. 1, 11 (2007) (citation omitted). Relying primarily on an earlier case, Barnett Bank of Marion Cnty., N.A. v. Nelson, 517 U.S. 25 (1996), the Watters Court clarified that “[s]tates are permitted to regulate the activities of national banks where doing so does not prevent or significantly interfere with the national bank’s or the national bank regulator’s exercise of its powers.” Watters, 550 U.S. at 12. “But when state prescriptions significantly impair the exercise of authority, enumerated or incidental under the NBA, the State’s regulations must give way.” Id.

{56} Two years later, in Cuomo v. Clearing House Ass’n, L.L .C., 557 U.S. 519, 523–24 (2009), the United States Supreme Court specifically addressed “whether the [OCC’s] regulation purporting to pre-empt state law enforcement can be upheld as a reasonable interpretation of the National Bank Act.” The Cuomo Court ultimately rejected part of the OCC’s broad statement of its preemption powers as unsupported. See Cuomo, 557 U.S. at 525, 528–29 (distinguishing the power to enforce the law against a national bank, which a state retains notwithstanding the NBA, from visitorial powers—including audits, general supervision and control, and oversight of national banks—which the NBA preempts as exclusive to the OCC). Although the Cuomo Court did not specifically address the preemption rule on real-estate lending at issue here, its rationale is nonetheless dispositive in its acknowledgment that “[n]o one denies that the [NBA] leaves in place some state substantive laws affecting banks,” id. at 529, and in its recognition that states “have enforced their banking-related laws against national banks for at least 85 years,” id. at 534.

{57} In addition, in 2010, Congress explicitly clarified state law preemption standards for national banks in Pub.L. No. 111–203, § 1044, 124 Stat. 1376 (2010) of the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. The Dodd–Frank Act preempts state consumer financial law in only three circumstances: (1) if application of the state law “would have a discriminatory effect on national banks, in comparison with the effect of the law on a bank chartered by that State,” (2) in accordance with the legal standard set forth in Barnett Bank when the state law “prevents or significantly interferes with the exercise by the national bank of its powers,” or (3) by explicit federal preemption. See id.; 12 U.S.C.A. § 25b(b)(1)(A)-(C) (2010).

{58} In response to this legislation, the OCC corrected its 2004 blanket preemption rule to conform to the legislative clarifications. See Dodd–Frank Act Implementation, 76 Fed.Reg. 43549–01, 43552 (July 21, 2011) (proposing changes to “the OCC’s regulations relating to preemption (12 CFR ․ 34.4) (2004 preemption rules) ․ to implement the provisions of the Dodd–Frank Act that affect the scope of national bank ․ preemption” by removing from Subsection a the blanket clause, “ ‘state laws that obstruct, impair or condition a national bank’s ability to fully exercise its Federally authorized [real estate lending] powers do not apply to national banks’ “ and by clarifying in Subsection b that “state law is not preempted to the extent ․ consistent with the Barnett decision”). Compare 12 C.F.R. § 34.4(a) & (b) (2011), with 12 C.F.R. § 34.4(a) & (b) (2004). Neither Dodd–Frank nor the corrected OCC regulations created new law concerning the scope of national bank preemption but instead clarified preexisting requirements of the NBA and the 1996 opinion of the United States Supreme Court in Barnett.

{59} Applying the Dodd–Frank standard to the HLPA, we conclude that federal law does not preempt the HLPA. First, our review of the NBA reveals no express preemption of state consumer protection laws such as the HLPA. Second, the Bank provides no evidence that conforming to the dictates of the HLPA prevents or significantly interferes with a national bank’s operations. Third, the HLPA does not create a discriminatory effect; rather, the HLPA applies to any “creditor,” which the 2003 statute defines as “a person who regularly [offers or] makes a home loan.” Section 58–21A–3(G) (2003). Any entity that makes home loans in New Mexico must follow the HLPA, regardless of whether the lender is a state or nationally chartered bank. See § 58–21A–2 (providing legislative findings on abusive mortgage lending practices that the HLPA is meant to discourage).

{60} Accordingly, we hold that the HLPA is a state law of general applicability that is not preempted by federal law. We recommend that New Mexico’s Administrative Code be updated to reflect clarifications of preemption standards since 2004.

III. CONCLUSION

{61} For the reasons stated herein, we reverse the decisions below and remand this matter to the district court with instructions to vacate its judgment of foreclosure.

{62} IT IS SO ORDERED.

DANIELS, Justice.

WE CONCUR: PETRA JIMENEZ MAES, Chief Justice, RICHARD C. BOSSON, EDWARD L. CHÁVEZ, and BARBARA J. VIGIL, Justices.